A few years ago, I wrote a paper trying to answer this question. In this series, we’ll find out.

I grew up as a white boy in a white family in the northern suburbs of Baltimore City. I was the youngest of her five children, including two adopted sisters and two biological brothers, who grew up in a lower-middle-class family. My mother graduated from the local gay Catholic high school, but she did not attend college. My father bounced around from school to school and never earned a diploma, earning his GED during a two-year stint in the Army Reserve at Fort Ritchey, Maryland, and finishing his military service just before the Vietnam War draft began. I did. He returned to his hometown and ended up becoming a city police officer for most of his professional life. My mother excelled in administrative work, and she spent her career as an assistant at various institutions, but her most beloved position was in the parish office of a Catholic church outside Towson.

My contact with people of color, particularly black Americans, was through my education with some friends on the street who were an ethnic byproduct of being born to a Caribbean-American mother and a German-American father. It was limited to classmates who became friends while growing up. Otherwise, as is the case with many white boys who grew up away from the effects of redlining, I learned how life was run in parts of town that I would never have known due to racism. The only thing we got a glimpse of was that, you guessed it, he was a hipster. hop.

The first CD I ever owned was a rap album featuring the experiences of two boys, each other’s namesake, wearing baggy jeans and jerseys backwards. Whether I’m telling a tragic story of missing the bus, never missing a bus again, or obeying the command “Jump!” I realized that I was with a man.[s]” and their experiences traveling the world as young black men. Despite our differences, there was something relatable in their words, and the New Jack swing that carried them was contagious.

Of course, like many white kids, I didn’t yet fully understand race and the divide between them at the age of nine, and I didn’t understand how artists like Criss Kross I also didn’t fully understand how race was factored into creating the version of life I painted on my synaesthetic canvas. Race existed on the periphery of my consciousness, but one day around the same time, or just before, I discovered resonance in rap music, it became more apparent.

My friend’s mother, a black woman from Guyana in South America, mentioned skin color in a conversation, but I can’t remember the context. I remember standing on my friend’s front porch during a mid-afternoon play break and Brenda pulling at her skin and telling me that she was actually brown, not black, and that I was actually He said he wasn’t white and had more pink skin. In other words, race is “created.” Alternatively, my adult interpretation is that the phenotypic categories we use to distinguish one another are arbitrary and therefore unreliable classifications.

It seems to me that the concept of race as a social construct and what kind of traumatic burden her racially codified body carries, given the colonization of the New World, , I couldn’t understand it at all. But as I became more conscious of my own whiteness, and the carefree days of my white youth faded with age and experience, what she was saying became clearer to me.what was But what was clear to me then was that most of the people darker than me were operating at the end of my insulated cul-de-sac in Baltimore’s frontier Lake Walker neighborhood. They were the ones who, if not directly, should watch over us and be on guard to make sure our bikes weren’t stolen or our bodies hurt. Still, it was their music and their stories that I wanted to hear, even if on a subconscious level, that resonated within me in an existential register.

The art of recording to a boombox was one I learned early in my musical journey when Baltimore rap radio station 92Q became a permanent fixture on the dial. I sat on the porch of my childhood home, next to a double-decker boombox, listening to the hooks imprint on both sides of a 90-minute tape like a pirate digging for buried treasure. The Pharcyde’s “Passin Me By,” MC Lyte’s “Roughneck,” Tribe’s “Award Tour,” En Vogue’s “Love Don’t Love You,” Salt N’ Peppa’s “Shoop” ”, and a faint echo of Queen Latifah’s refrain can be heard. “UNITY” broke through the fog of my memories as I entered middle age. My neighbors were excited to see Running Man shamelessly displayed under my porch steps. It wasn’t so much that I was showing off, but that I couldn’t resist the beat’s temptation to invade my physical movements, even if it meant public weakness.

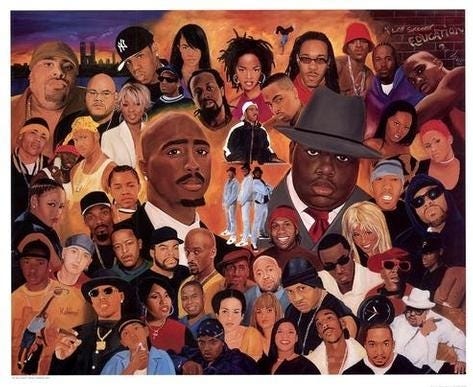

Since then, hip-hop has shown what it means to be black in a white world through percussive wordplay, personal stories, styles, songs, scholarship, dance, and the timeless art of graffiti. It continues to hold its own as a cultural movement and musical genre. This book is important in terms of my music choices, how I interact with the world, and how I live in a cisgender white male body.

This is where, at age 50, I pause to find my pocket in the timeless beats, rhymes, and rhythms of life. Just to see where I fit into the code. Hip-hop is American history, emerging from the nightmarish shadows of white men’s dreamscapes. In fact, it is a ground reality, told from a subaltern space of meaning-making that exists outside mainstream modes of communication. It is an underground thing, alchemized in the melting pot of racist militancy and from which evolved the golden age of culture that we are lucky to live in.

Hip-hop’s Black history and reflectively relating hip-hop to hip-hop as Black history is a practice of racial formation on a personal level that explains all the ways in which I appropriate and consume Blackness. This is meta-mindfulness.American cultural creativity inspires me American blackness Because it exists within my culturally conditioned performance. It is a radical reformulation of my identity as a white, cisgender, gay man, not in a blackface minstrel way, as it exists in and through my whiteness. As a matter of fact. In this way, the simple act of listening to rap music and dancing to its beats turns into gradually unfolding psychological layers. A sufficiently deep discovery reveals a human being stripped of all socially sanctioned defenses against the death threats that people of color pose in the white imagination.

As a hint, hip-hop is not just a category of creative cultural output, but also a lifestyle that carries a special responsibility for white people who choose to participate in hip-hop to act for racial justice. For white people whose enjoyment of black culture forever straddles a fine line between “love and theft” (Lott, 2013), hip-hop is a way to identify themselves as white and to re-express their whiteness as white. This is a call to action to make efforts. something that is not oppressive and false, something that is liberating for us and others, in words and deeds (Davis, 2014). In this way, the cultural practice of hip-hop becomes, at its best, a method of racial self-identification with political implications.

Through this multi-part narrative essay, I will work to unpack the notion that white people can actually embody hip-hop without condoning the murderous acts of historical erasure. I place particular emphasis on my own narrative as a representative of white hip-hop whose formal study and participation in hip-hop culture has shaped my ethical efforts. Specifically, it prompted a lifelong investment in disrupting the circulation of what my mentor, theologian Christopher Driscoll, calls “white religion” (Driscoll, 2016). White religion is a collective practice of ritualized behavior centered on acquiring privilege and power for white people. It’s white.

As alluded to above, the theory of a “hip hop underground” (Peterson, 2014) allows white people to develop their own position within hip hop without falling into the double trap of blind consumption and hip hop. This will provide a driving force for a better understanding of how we can successfully manipulate the Unconscious appropriation. In the course of this conversation, I develop a framework for thoroughly thinking through and reifying the black meaning of hip-hop culture as an “underground” practice of white identity formation.

Then we go down to the basement.